In my short time as a trauma program manager, I have seen significant turnover among my peers. Several TPMs I met in just the last two years have already moved on to other roles. Many others appear to be contemplating a career change. What’s the problem? One big reason appears to be workload.

The Trauma Center Association of America (TCAA) recently published an “Ask Traumacare” report addressing this very issue. The Trauma Program Manager Workload report is based on survey responses from nearly 200 TPMs nationwide. (TCAA members can access the report here.) These respondents report long hours, growing responsibilities and often negative effects on their health and personal lives.

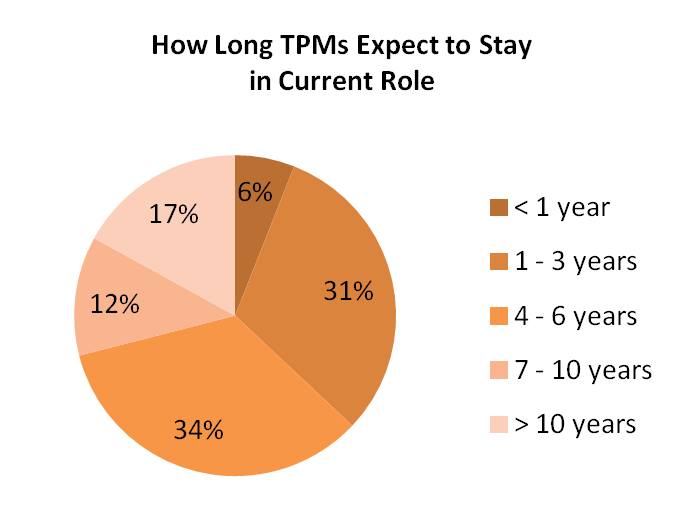

All of this seems to have a big impact on turnover. According to the report, 71% of TPMs do not plan to stay in their current position for more than 6 years. Within that group, more than half do not expect to remain more than 3 years.

When I received this report, I spent a lot of time thinking about it. As a relatively new TPM, I wanted to understand the issues that might cut my trauma career short. Most of all, I wanted to learn what I can do to make sure I feel as excited about trauma 20 years from now as I do today.

Following are some thoughts on how trauma program managers can respond constructively to the unique pressures we all face.

1. Take the stress out of surveys with early preparation

Whenever I see a job opening for a trauma program manager, I can’t help but wonder whether the outgoing TPM had just suffered through an unsuccessful survey.

In the eyes of hospital administration, the TPM’s sole responsibility is to pass the state trauma designation survey or the American College of Surgeons (ACS) verification review. And in a way, they are correct. I define my role as improving the care of the trauma patient. One way I can ensure proper trauma care is to meet state and ACS trauma guidelines.

What is not well understood by many hospital administrators is that trauma verification and designation surveys are extraordinarily rigorous. There are many moving parts in a trauma program. When they are not all working together, the program may crumble.

The TPM is most often the one who takes the brunt of a bad survey. The trauma medical director generally works in the trauma program in a part-time capacity, so responsibility for a survey falls mainly on the fulltime TPM. It can be frightening to think that you are one bad survey away from losing your job. I am convinced that this atmosphere is one important factor that pushes talented people out of trauma program management.

What can you do to manage this stressful situation? For me, the keys are ongoing preparation and consistent communication. Focus on the issues that matter the most. As everyone knows, a single Type 1 deficiency will fail an ACS trauma survey. If you don’t have proof that your facility meets all Type 1 criteria, you might as well not invite the ACS to come and review your facility.

- One year before your survey, conduct a gap analysis to see what areas you need to work on. Look at every criterion from the Orange Book related to your trauma center level and write a brief description of how you are meeting that standard.

- Be very transparent with this information. Present your initial analysis to your hospital’s chief nursing officer and other members of the executive team and follow up with regular updates.

- Meet monthly with your staff to review your progress toward survey readiness.

- In addition, conduct one or more full mock surveys (with mandatory attendance) to uncover weaknesses and identify ways to increase your survey readiness.

There is sometimes leeway as to when a survey needs to take place. In these cases, the TPM must speak up and be an advocate for the trauma program. If your program isn’t ready for a review, then don’t have a review.

2. Improve your work/life balance by building a high-functioning team

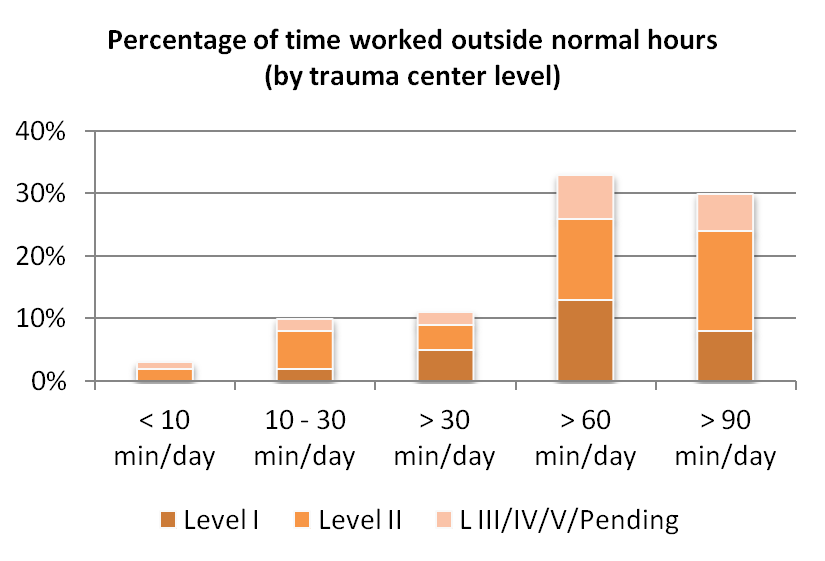

According to the TCAA report, the majority of trauma program managers work an extra hour every day. About one-third work an additional 90 minutes. One in ten feel their workload has increased over the last year, and 97% report coming in early or staying late to keep up with all their work responsibilities.

I have found that my “extracurricular activities” have only increased as I have progressed in my role. I often find myself answering e-mails off hours because I know I won’t be able to get to them during the week. I also find myself coming in on weekends to prepare for Monday morning trauma rounds. And I know what it takes to achieve a successful survey, so I put in the extra time to ensure that happens.

But the extra hours have a cost. Nearly half of TCAA survey respondents feel their workload affects their health (47%) and that their job negatively affects their family, religious or cultural responsibilities (49%). When asked about issues that could prompt them to leave their job, the number one response (40%) was lack of work/life balance.

What’s the solution? In our field, we often say that “trauma is a team sport.” However, when it comes to managing a trauma program, we seem to forget that. If any of us is going to survive in this role for long, we need to keep in mind that the weight of the entire trauma system doesn’t have to fall on our shoulders.

For example, most TPMs know that when you take a day off, the work tends to pile up for later. While this may be true to a certain degree, I have found that the pile-up can be eased if you have a high-functioning team.

I have made a point to train my team members to perform some of my responsibilities. That way, when I must be away from the office, mandatory work can continue. For example, staff members can be trained to thoroughly review charts, help prepare meeting agendas and assist nurses with charting in the trauma bay. If your team has the right tools and training, the program won’t derail in your absence.

Another strategy for improving work/life balance is making room for aspects of your job that you truly love. For example, I am really energized by being involved in youth injury prevention programs. My team has run several trauma simulations for high school students. Watching students experience these simulations and debriefing with them later is an experience that makes you feel like you are positively impacting the community.

3. Use education and communication to secure administrative support

Many of the frustrations of trauma program management stem from lack of support. In many hospitals, executives do not provide adequate financial resources or leadership support for important trauma program goals and needs.

A big part of this problem is an overall lack of understanding of what a trauma program does. It is hard to support something you don’t understand. That’s why it is the duty of the TPM to provide continuing education to the C-suite team.

The first priority is establishing a high-level understanding of the trauma world. To educate hospital leaders on this topic, I created a presentation that I call “The Circle of Trauma.” This presentation helps explain what makes trauma care unique, with an emphasis on the importance of systems of care and a team approach. It also underscores the different ways the entire hospital benefits from the presence of a trauma program.

I have presented my “Circle of Trauma” talk to hospital executives and managers, board meetings, community provider groups, and others. In my experience, this modest education effort helps build understanding and secure support for trauma program goals.

It is also important to keep hospital leaders in the loop with operational updates. This may be as simple as copying administrators on key emails. As I noted above, my team provides regular survey readiness reports to the CNO and sometimes the chief medical officer as well.

Another strategy is to do your best to run the trauma program as a business. If trauma does not maintain an operating margin compatible with the needs of the organization, it can be very difficult to maintain strong administrative support.

In this area, the TCAA is an invaluable resource. Traditionally, trauma centers lose money, but with help from the TCAA I have been able to establish appropriate charges for trauma patient care. Proper trauma charges are key to creating a self-sustaining program and earning leadership support.

4. Limit the additional duties you can, and manage the ones you can’t

By definition, a trauma program manager wears many hats. The job typically includes PIPS meeting coordination, state trauma council participation and many other responsibilities. Recently, I was reading discussion posts on the Society of Trauma Nurses website. As I scrolled through, I began counting all the additional titles that trauma program managers have — disaster coordinator, ED/ICU liaison, organ donation coordinator, EMS coordinator, helicopter coordinator, burn coordinator and others.

The administrative workload also seems to be growing. According to the TCAA Trauma Program Manager Workload report, TPMs say that paperwork is increasing. Nearly half of trauma program managers have responsibility for patient satisfaction scores and about two-thirds are tasked with managing patient complaints. Another big area of responsibility is the registry. About half of TPMs not only oversee the trauma registry, but are responsible for performing registry-related tasks.

It’s difficult to manage a trauma program when true TPM tasks are only a portion of your job. What can trauma program managers do to minimize the additional responsibilities that dilute their focus?

First, sharing is caring. As I discussed above, it is possible to manage extra duties by training your staff to share the workload. To do this, invest in the proper tools and training for your team. A team that spends a lot of time together will tend to pick up on each other’s strengths and weaknesses. Use this valuable knowledge to assign tasks to match team member strengths.

Second, if at all possible, turn data management over to dedicated trauma registrars. Are you entering registry data as a TPM? This may be required in a Level III or IV center, but in a busy Level I or II center (and in some Level IIIs) data abstraction and entry must be done by a properly trained registrar. Registrars I have worked with are much more efficient at this task, but they are not without their challenges. Even the most skilled registrar cannot escape the time-consuming work that ICD-10 has brought on.

From a Trauma System News Sponsor:

Is your program struggling with a trauma registry backlog? Schedule a free consultation with a trauma registry expert to get customized guidance on how to catch up. I want to know more.

Third, it may be possible to minimize your extra duties by utilizing other resources already in place. In a trauma program I managed previously, we did not have a full-time injury prevention coordinator. However, we did have a robust hospital injury prevention program. While not all the activities of this program were transferable to trauma, we were able to leverage this resource to launch community-focused injury prevention initiatives.

5. Take responsibility for your professional growth

In terms of career potential, trauma program management has an inherent problem. How can you get promoted if you are already the manager? Lack of a clear path forward may be one reason many talented TPMs end up leaving the trauma world.

In my opinion, trauma program managers cannot count on others to lay out a career path for them. The only way you can address this limitation is to assume personal responsibility for your own professional growth.

In some hospitals, there may be an opportunity to become trauma program director. This job is often an umbrella role that also has responsibility for emergency and critical care services, so it is important to continue both your trauma education and your professional education.

Seek professional nursing board certifications and encourage them for your staff. If your program participates in the Trauma Quality Improvement Program (TQIP), it makes sense to attend the Annual Scientific Meeting and Training. The TCAA also offers a full range of opportunities to develop your leadership skills and your expertise in every aspect of trauma program management.

It’s worth it

Being a trauma program manager is tough, but we all know how satisfying this job can be. There are a lot of challenges that push talented people out of trauma program management. But taking steps proactively can help ensure that we all thrive in this important and rewarding role.

Bryce M. Bishop, RN, TCRN, CFRN, CEN, CPEN, NREMT is the trauma program manager at Rochester General Hospital in Rochester, New York.